The context of this article is a reflective, fictional narrative that explores the experience of therapy for someone, through the lens of waiting and anticipation before an analytic session. It emphasises the sensory and thoughtful environment surrounding psychoanalytic therapy — from the physical space of the waiting room to the inner process of introspection and reflection that occurs differently for each one. Through sensory descriptions, the article conveys how a person may think about their analysis, awaiting not only the words, meanings and interpretations, but also their own thoughts and feelings. The setting, sounds, and the act of waiting are metaphorically tied to the anticipation of therapeutic conversations surrounding encounter, reflection and speech in therapy.

Waiting rooms. He’d sat in many, of course, he had. In the quiet, sterile limbo between anticipation and action. The hum of the air conditioning, the ticking of the clock. Sometimes, the smell of antiseptic or stale coffee lingered in the air. He’d sat in these rooms, waiting to be called — to be seen, to be fixed, or perhaps just acknowledged. But lately, he’d been waiting for something else entirely — to be heard. Not merely listened to, but truly heard.

This time, he had found himself in Melbourne. Still. And stillness. It had been a Tuesday, he thought. He was on his way to see a psychoanalyst, in person. Not through a screen. No distance, no delays. Just a door. A room. A body. He couldn’t remember how tall the analyst had been, how he moved. Seeing him again — all of him — had reminded him of those strange reunions after years of absence, like encountering a family member after lockdown or finally meeting someone in the flesh after months of digital exchanges.

The building stood in the heart of Carlton. Old but not ancient. It breathed history in a subtle way, lived-in, softened by time. Each visit, it seemed to whisper a new scent — incense, cleaning fluids, or sometimes something else entirely, depending on the day. On his first visit, as he stood outside, fumbling for the entry code, he had heard Persian music drifting through the air — Googoosh or maybe Hayedeh — like something from the past, swirling through the city streets. Was it real, or was it the city, remixed? A soundtrack of memory?

The next day, the analyst had sent him out to the heart of the city, to Bourke Street Mall. He’d lost his phone there. Typical. But a stranger had returned it. He’d found it at a small kiosk, the attendant unmistakably Iranian. The man had handed him his phone, along with a note, folded carefully in his hand. It was written in Farsi:

“این نیز بگذرد” — This too shall pass.

“My favourite saying,” the man had said. “A friend gave it to me. Now I’m giving it to you.”

He’d smiled faintly and added, “There aren’t many of us here.”

Perhaps there had been more than he thought. Maybe he had been hearing Persian whispers all along — woven into the fabric of Melbourne’s urban soundtrack, the hum of a language long-forgotten, yet still somehow present.

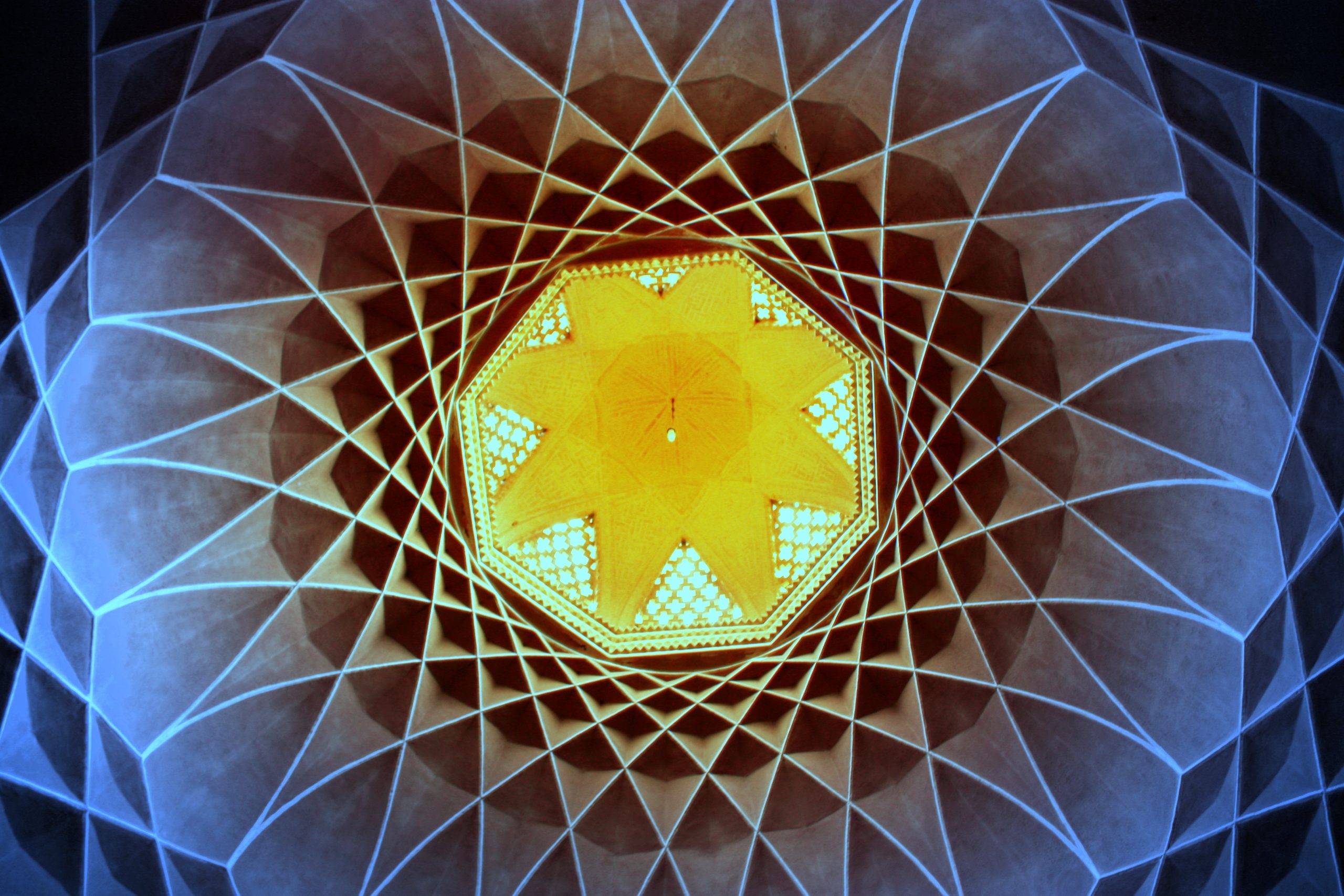

He remembered sitting in the waiting room now. Not the office — before the office. That liminal space. The waiting room had always been a space between, a threshold. A place of suspension. A couch. A window. A few bookshelves. An alcove carved out of the wall — a taagh-cheh, reminiscent of his grandparents’ house in Berlin. The shelf had held a red cloth, patterned with thin white lines. He’d stared at it for what felt like hours, lost in memory. It had been strangely familiar. He had once owned a similar cloth, bought during a trip to Hamburg — he had worn it wrapped around his hair. A bus driver on the outskirts of Nuremberg had asked him if he was from Düsseldorf. “You have the sun in your skin,” he had said. But he had been from Berlin. Or at least, he had thought he was.

He’d checked his watch. Only two minutes had passed, yet it had felt like a lifetime.

Tick. Tick.

Tikkeh. A fragment. A piece of time. The word itself had become a symbol, each second stretching into eternity.

Outside, a breeze had stirred the curtain, carrying with it the scents of the city. It had been a soft, cool wind — the kind he had felt by the water in Hamburg. Light had filtered through the lace, casting shifting patterns on the floor. He’d looked out the window. Across the street, a boy had stood in an apartment, his face faintly visible, a ghost of a memory he couldn’t quite place. Had he seen him in Munich? Or was it Frankfurt? Maybe both. The line between them had blurred.

The shelf in the alcove had held pottery — simple, honest, earthy. No fine porcelain or pretension, just the raw beauty of handmade things. It had reminded him of his uncle’s home in rural Germany, where the shelves had been filled with similar objects, each one holding its own story. The only difference here had been the rugs. They had been plain, utilitarian. No Persian knots, no floral motifs. He had found a strange relief in their simplicity. This hadn’t been home. And perhaps, he hadn’t wanted it to be.

And here — Melbourne — what had this place been?

A city of wind, light, and trams.

A city that blurred the boundary between presence and absence.